Building of the Month - April 2018

Ballysakeery Glebe House, hidden from view on a tree-lined road branching off the R314 from Ballina to Killala in north County Mayo, boasts a strong connection with the 1916 Rising as the birthplace and childhood home of Dr. Kathleen Lynn (1874-1955), Chief Medical Officer at the City Hall Garrison. Owing to its architectural and historical significance, the glebe house received funding from the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht under the Structures at Risk Fund 2016 for emergency repair works intended to bring the structure back from the brink of ruin and to prevent the further deterioration of its surviving original fabric. The glebe house was the recipient of further funding from the Department under the Structures at Risk Fund 2017.

Ballysakeery Glebe House: Early History

Ballysakeery Glebe House can trace its origins back to the early nineteenth century when ‘a new church [for] the parish’ was erected ‘on a new and more central site’ in Lisglennon townland. Ballysakeery Church was one of almost seven hundred Church of Ireland churches built or rebuilt between 1808 and 1823 with the financial support of gifts or loans from the Board of First Fruits (fl. 1711-1833). The Board, a Church of Ireland institution deriving its income from tithes payable irrespective of religious persuasion, was established by Queen Anne with the express purpose of building churches and glebe houses and, in respect of Ballysakeery parish, gave a gift of £400 and an equal loan of £400 for the construction of a glebe house in the neighbouring townland of Mullafarry.

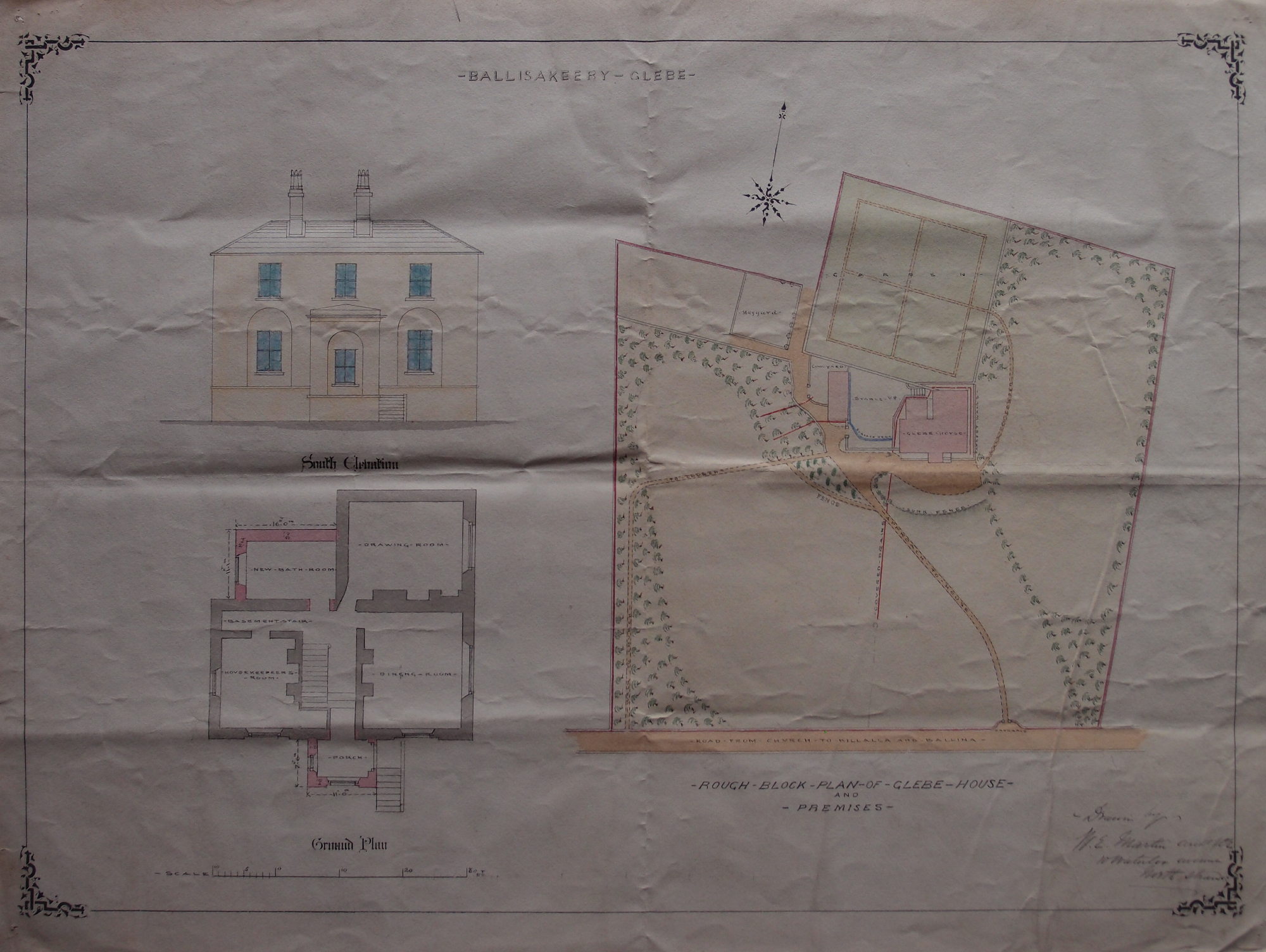

The architect of the glebe house is unknown, however, surviving drawings in the collection of the Representative Church Body Library show the elevation, basement and ground floor plans ‘of a Glebe House to be built on the Glebe of the Parish of Ballisakeery [sic] in the Diocese of Killalla [sic] by the Revd. Joseph Verschoyle Vicar of the united Parishes of Ballisakeery [sic] & Rathrea’. Conveniently, Reverend Joseph Verschoyle (1794-1867) was the son of the Right Reverend James Verschoyle (1750-1834), Bishop of Killala, whose note states: ‘I approve of this Plan & authorise the Vicar to commence the work 1st August 1815’.

A chimney stack placed front and centre in the roof served fireplaces on either side of the central hall and, effectively hovering over a void, was carried on an arch spanning the first floor landing. A later drawing signed by William Edward Martin (1843-1915) of 10 Waterloo Avenue, North Strand, Dublin, suggests that it was once contemplated to replace the central stack with chimney stacks on either side of the hall but this was never carried into effect. The drawing also shows, shaded in pink, the porch and bathroom added to the glebe house in the 1860s.

Dr. Kathleen Lynn (1874-1955)

Reverend Robert Young Lynn (1844-1923) was appointed rector of Ballysakeery in the early 1870s. Lynn and his wife, Kathleen Marian (née Wynne) (1840-1915), welcomed a daughter, named Kathleen Florence, on the 28th January 1874. Kathleen’s place of birth is often given as Cong, south County Mayo, where the family moved in 1886 and where Reverend Lynn served as rector until his death in 1923. However, Kathleen specifies Mullafarry Co. Mayo in the Household Return Form of the 1911 National Census and begins her Statement by Witness (1950) thus: I was born in Mallaghfarry [sic] in Mayo, two miles from Killala, where my father was a clergyman.

The young Kathleen, affected by the conditions of the poor in the west of Ireland, vowed to become a doctor and, completing her studies at the Medical School of the Catholic University of Ireland in Cecilia Street, received a degree from the Royal University of Ireland in 1899. Following her graduation, and internships in a number of hospitals across Dublin, Dr. Lynn set up private practice in her home at 9 Belgrave Road, Rathmines. Constance Markievicz (1868-1927), a distant cousin, contacted Dr. Lynn ‘about 1912 or 1913’ to treat Helena Molony (1883-1967), activist and member of Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and it was during her convalescence at Belgrave Road that Molony encouraged her host’s interest in politics. Dr. Lynn later recalled ‘We used to have long talks and she converted me to the National movement. She was a very clever and attractive girl with a tremendous power of making friends… I had become interested in the Women’s Suffrage Movement before that…and quite sympathised with the militant side of it’.

As a member of the Irish Citizen Army, Dr. Lynn spent the weeks leading up to Easter 1916 assisting James Connolly (1868-1916) in reconnaissance and Willie Pearse (1881-1916) in munitions smuggling in preparation for a Rising ‘coming off altho’ we did not know the exact date…we knew from the precautions that were being made that it could not be far off’. On Easter Monday Dr. Lynn received her commission as a Captain and Chief Medical Officer and was ordered to report to City Hall. Once City Hall was re-taken by British forces, Dr. Lynn was arrested and detained in Ship Street, Richmond Barracks, Kilmainham Gaol where she could hear the execution of the 1916 leaders, and Mountjoy Prison where she and her fellow detainees were interviewed by the American press. Dr. Lynn was eventually deported to England where she worked as a locum in Coltford and Bath before returning to Ireland.

Dr. Lynn was elected as Vice-President of Sinn Féin in 1917 and was elected to Dáil Éireann in 1923 representing the South Dublin constituency. Losing her seat in June 1927, and failing to win a by-election the following August, Dr. Lynn abandoned her political career in order to concentrate on her work at Saint Ultan’s Children’s Hospital [Teach Naomh Ultuin] which she co-founded with Madeleine ffrench-Mullen (1880-1944) in 1919. Dr. Lynn died on the 14th September 1955 and was buried with full military honours in the family plot in Deansgrange Cemetery.

Ballysakerry Glebe House: Later History

Following Reverend Lynn’s transferral to Cong, Ballysakeery Glebe House continued to serve the incumbent of the parish and the Household Return Form of the 1901 National Census gives Reverend John Perdue (1855-1946), his wife Mary Isabella (1859-1924), three sons, and a servant named Mary Quigley, as residents. The 1911 National Census saw the glebe house occupied by a diminished household of Reverend Perdue, one son, a niece, and a servant named Norah Lowin. An auction of furniture and household effects, held in March 1925 on the instructions of Perdue, described the glebe house as containing a hall, a dining room, a drawing room, and three bedrooms together with a kitchen and stores in the basement. The last resident incumbent, Reverend Francis Kenny (c.1868-1933), was appointed to the parish in 1929 and, on his death, the glebe house was vacated and the contents sold. A decline in parishioners saw Ballysakeery Church close and the glebe house pass into private ownership. The glebe house eventually formed part of a bank of land purchased for the development of the Asahi Synthetic Fibre Plant (1977) and, neglected and unoccupied, began its descent into disrepair.

Ballysakeery Glebe House: Restoration

The first glimmer of hope for a brighter future came when the glebe house passed into the ownership of Mayo County Council, however, a detailed analysis by Southgate Associates revealed a structure in a perilous state with a roof on the point of collapse, walls showing evidence of long-term water penetration, structurally unsound chimney breasts, subsiding floors, and broken or missing windows. The interior, similarly dilapidated and subjected to theft and vandalism, nevertheless retained features of interest, particularly in the dining room, including door and window architraves and simple moulded plasterwork cornices.

A tender for stabilisation works was advertised in June 2016 and, although it was anticipated that the works would include both the glebe house and the adjacent stables, the resources available allowed for the stabilisation of the glebe house alone. Once scaffolding was in place, a close inspection of the roof was made, confirming that the central chimney stack and its supporting arch were in a precarious condition: indeed, light was visible through the stone work at various points. Sections of slate and the underlying timber work were also loose or missing.

The first stage of the restoration saw the entire roof stripped back to its timber skeleton with the original slate and ridge tiles carefully stacked and stored for later reused. Similarly, the limestone of the central chimney stack was numbered and carefully dismantled to allow for a faithful reconstruction with each stone returned to its original position. Among the interesting features uncovered during this process were the various marks stamped into the head of the nails (“VIII”), the chimney pots (“GARNKIRK”) and the ridge tiles (“R. ASHTON & Co. BUCKLEY FLINTSHIRE”).

Once the supporting arch had been inspected by a conservation engineer, the central chimney stack was reconstructed and repointed using a lime mortar. As many of the original slates as possible were reused. Damaged or defective slates were re-cut for use on the angles of ridges and valleys. A gablet was also repaired with surviving fragments of the original timber bargeboards used as templates to create a suitable replica. The glebe house could now boast, for the first time in many years, a watertight roof. The installation of new rainwater goods brought the first stage of the restoration to a satisfactory conclusion. Plywood sheets on the doors and windows, perforated to allow for ventilation, will allow the glebe house to gradually dry out in advance of the next stage of restoration.

The first stage of the restoration of Ballysakeery Glebe House was supported by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht under the Structures at Risk Fund 2016. The glebe house received additional support from the Department under the Structures at Risk Fund 2017.

Ballysakeery Glebe House: Restoration Update (2023)

The phased restoration of Ballysakeery Glebe House has progressed since this Building of the Month was first published in April 2018. The repair of the roof of the return was completed in 2020 and, in addition to the repointing and refinishing of the chimney, saw the installation of new cast-iron gutters and downpipes. The plaster below, damaged and stained by damp, will be renewed in a later phase of works.

The porch designed by William Edward Martin has been removed in preparation for the full restoration of the façade to its original 1815 appearance.

The restoration has taken in an adjacent outbuilding which, according to a plan in the Representative Church Body Architectural Drawings Collection, was designed to house stables and byres either side of coupled carriageways. The multi-purpose outbuilding also included nesting boxes in eye-catching diamond formations. The outbuilding was an overgrown ruin in 2010 but ivy has been cleared, brick work has been repaired and, most importantly, it has been made largely weather-tight by the construction of a new roof.

David Hicks works with Bourke Builders of Ballina who specialise in the conservation of historic buildings and who, in addition to the first stage of the restoration of Ballysakeery Glebe House, have carried out works on McKee Barracks and the Lower House, Grangegorman, Dublin. David is the author of Irish Country Houses – A Chronicle of Change (2012) and Irish Country Houses – Portraits and Painters (2014). David has conducted extensive research on the architectural heritage of his native County Mayo and publishes regularly on his blog

Back to Building of the Month Archive