Building of the Month - December 2021

Distilling has been an important part of the economy of Cork since the late eighteenth century and, with the production of gin and whiskey taking place in several sites around the city, the industry has been a significant employer for over two hundred years. Four of the largest distilleries – Daly’s Distillery, Green Distillery, North Mall Distillery and Watercourse Distillery – amalgamated in 1867 to form the Cork Distilleries Company (CDC): the company was joined by Midleton Distillery in 1868. The largest and most profitable plant was based in North Mall on an island on the north bank of the River Lee. A calamitous fire in 1920 destroyed the Victorian mill and caused significant damage to much of the surrounding site. The disaster coincided with a moment of crisis for the distilling industry, not only in Cork but throughout Ireland, and, in the face of economic uncertainty, the company opted not to rebuild or renovate but to move production of the elixirs to the plant in Midleton. The industry eventually recovered, although many smaller concerns fell by the wayside, and, demand beginning to outstrip supply, the limitations of the Midleton site became increasingly apparent. This spurred the company to reconsider the dormant North Mall site and its potential for redevelopment as a bottling plant and dispatch warehouse for Cork Dry Gin and Paddy Whiskey. A state-of-the-art facility was required, not only for operational reasons but to promote the image of the company and its heritage-rich products as relevant to the contemporary Irish lifestyle, worthy rivals to Jameson and Powers, their Dublin-based competitors (fig. 1). It came as no surprise then when, in 1960, CDC appointed Frank Murphy (1916-93) to design the new North Mall plant (fig. 2).

Murphy, a graduate of University College Dublin in 1939, was part of a circle of architects and artists deeply rooted in the modern movement, keen to explore contemporary architecture on the continent and in the United States, and equally keen to adapt it to an Irish context. Murphy had a particular interest in Scandinavian architecture and chose to honeymoon in Sweden in 1947 owing to the abundance of modern architecture he could discover there. He revisited for three months in 1951 and again in his capacity as an envoy for Bord Fáilte Éireann promoting tourism in West Cork. These trips gave him ample opportunity to study the work of Alvar Aalto (1898-1976), Gunnar Asplund (1885-1940), Sigurd Lewerentz (1885-1975) and others who sought marry contemporary architecture with the natural landscape. By the early 1960s his attention seemed to turn more towards American and British architecture and he was an admirer of the General Motors Technical Center (1949-55), Michigan, by the Finnish-American Eero Sarrinen (1910-61) which used colour as a device for visual separation of large zones. He was also attracted to the work of the British Brutalists, Alison Smithson (1928-93) and Peter Smithson (1923-2003), and their emphasis on expressing internal functions graphically on external elevations.

Murphy’s practice, opened in 51 South Mall the year after his graduation, was built on commissions from commercial companies and religious institutions, mostly in his native Cork, which included the Dutch-influenced Jennings Soda Water Factory (1949-50) on Watercourse Road, the Chicago-esque Shield Insurance Building (1950) in South Mall, and the Scandi-styled Presentation Convent and National School (1952-7) in Ballyphehane. Murphy produced an early masterpiece with All Saints Catholic Church (1953-6), Drimoleague, which has been described by Richard Butler as West Cork’s first modernist building. By 1961, when approached by CDC, Murphy was one of the most in-demand architects in Cork and had a staff of thirty in his studio.

Murphy approached the North Mall plant with a dedication unmatched by his earlier commissions, designing and supervising the project almost entirely by himself, perhaps because, coincidentally and poignantly, the site was a stone’s throw away from the house on North Mall where he was born and raised. Murphy’s first task was to consolidate the site in preparation for its redevelopment. The facilities that had survived the fire of 1920 were ruined, unconnected and uncoordinated and Murphy seized the opportunity to reorder and synchronise, repurposing existing buildings, including the bond stores, and introducing new elements such as a small gate lodge. The original North Mall Distillery faced the city but, the site now prepared, the new bottling plant was given pride of place overlooking the River Lee.

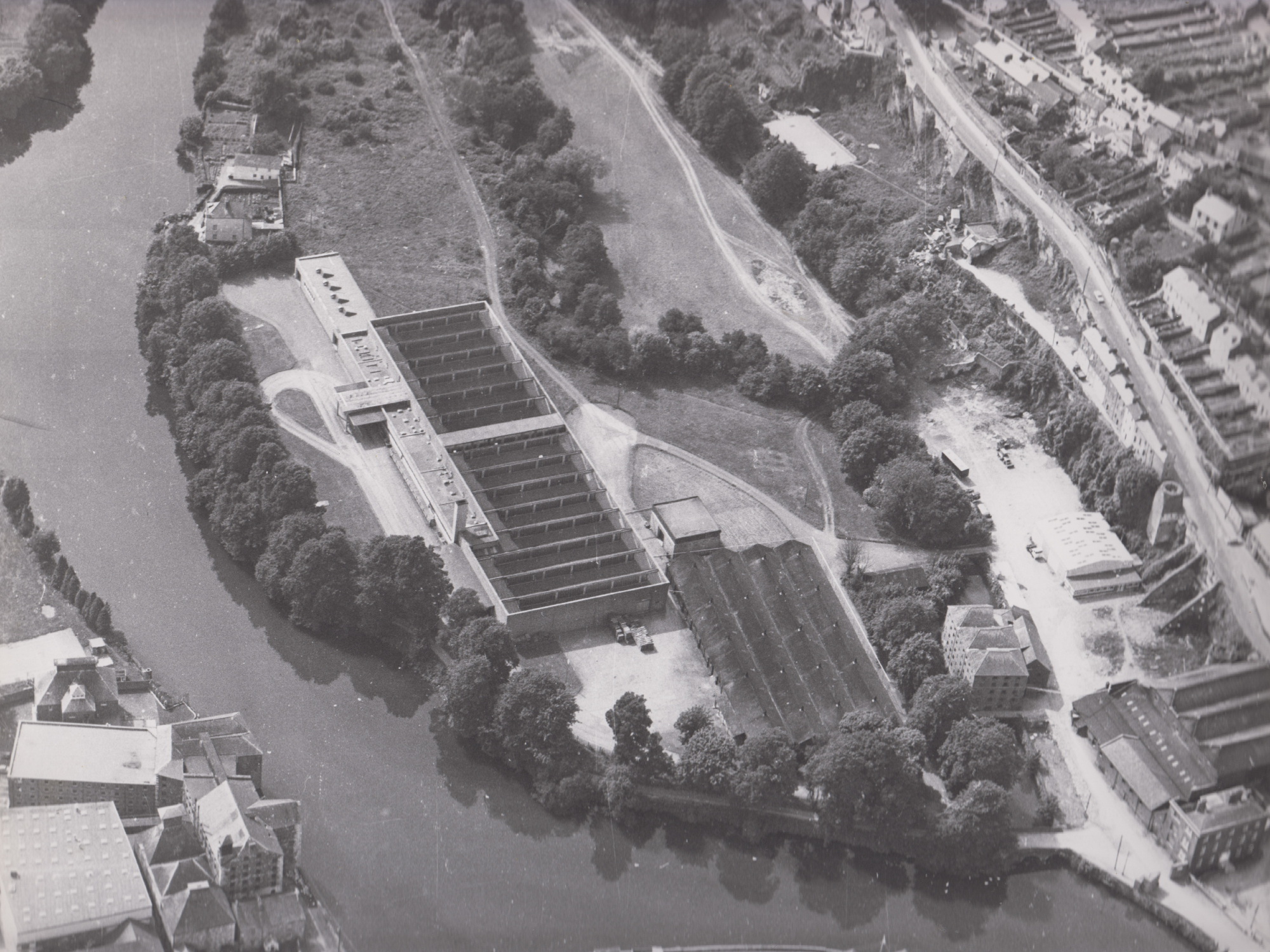

The bottling plant is long and low – Murphy insisted it should be single-storey in deference to the urban scale of the city – and it is difficult to appreciate its full extent unless viewed from a slight distance from the opposite side of the river. It is made up of several “zones”, the top-lit open plan bottling hall spanning the entire length of the building, the offices and canteen at the front framed by the cantilevered canopies of the goods-in and goods-out loading bays (fig. 3). The predominant building material is a pale russet-coloured concrete block, roughly rusticated, but Murphy skilfully avoided monotony by drawing on Sarrinen and the Smithsons and using palette and pattern to animate each “zone” and give it its own identity.

The office and canteen “zone” is identified by a sequence of concentric planes and frames beginning with an elongated horizontal window at its centre, a filmstrip of sorts, where aluminium fittings are set within a precast concrete frame. This gives way to bright yellow glazed brick – a tip of the cap to the glazed ceramic tiles synonymous with Victorian breweries and distilleries – with a margin of vertical soldiers. The sequence concludes with an outer plane of concrete block with precast concrete coping. The office and canteen “zone” is lower than the bottling hall behind it and, entered by way of a raised walkway on upturned pyramidal piers, gives the impression that it is floating (fig. 4).

The goods-in and goods-out loading bays on either side are sheltered by half-cantilevered canopies on remarkably slender piers, which, ingeniously, have ducted pipes to carry rainwater from the roof to drains below. The taller of the two adopts the guise of a rigid ripple of water, the reinforced concrete chevrons matching, in profile, the concertina folding doors below (fig. 5). The loading bay closest to North Mall is of cast concrete with a semi-elliptical fluted underside. A symmetrical concrete framework filled with glass blocks gives much needed light to the working space behind (fig. 6). The expressive canopies give vertical thrust to the bottling plant, countering the elongated superimposed horizontals, and, in another nod to Victorian factories, are joined by a soaring chimney stack rising above the surrounding treetops.

The heart of the bottling plant, the enormous bottling hall, eliminated the need for structural piers or pillars by using gargantuan steel beams, thirty metres in length, to support the fourteen saw tooth-profiled roofs overhead. This feat of engineering was designed by Edwin Uniacke who joined Murphy’s practice in 1953, becoming partner in 1965, and is best appreciated from within as only the crowns of the teeth are visible above the parapet.

The stark outlines were mitigated by soft landscaping with precast concrete planters around the base of the office and canteen “zone”, kerbed lawns which over time included perennials and shrubberies, and the shelter bed of trees which give tantalising glimpses of the bottling plant from Saint Vincent’s Bridge and The Mardyke (fig. 7). The Classical Revival City Hall (1932-6) is often referred to as the last of the Gandon-style monuments in Cork but Murphy’s industrial masterpiece can stake a claim to that title, benefitting from, and giving a unique sense of place to its setting on the River Lee.

Murphy’s work became increasingly diversified in the 1960s and covered a broad spectrum of commissions including Thompsons Bakery (1962-7) in MacCurtain Street; his own home, Tír na nÓg (1964-5), in Blackrock; and Sutton House (1966-7), South Mall, the first purpose-built office block in Cork. As his practice continued to win prestigious commissions in the 1970s, Murphy took a step back, acting as a frontman for the company but ceding creative control to his team so that he could dedicate his efforts to his other passion: the protection and restoration of Cork’s architectural heritage.

The future of Skiddy’s Almshouse (1718-9), the oldest continually occupied charitable building in Cork, was put in jeopardy in 1966 when the trustees of the charity moved to new premises on Pouladuff Road and sold the site to the North Infirmary Hospital for redevelopment. Murphy was alarmed at the potential destruction of an irreplaceable architectural gem and established the Cork Preservation Society in 1968 with the express purpose of raising funds to purchase Skiddy’s Almshouse for the benefit of the people of Cork. Drawing on a wealth of professional contacts and well placed supporters, including An Taoiseach Jack Lynch (1917-99), Murphy supervised the rehabilitation of the almshouse as fifteen self-contained apartments, the completion of the project in 1975 coinciding with the European Architectural Heritage Year aimed at fostering an awareness of and an appreciation for our architectural heritage.

Almost fifty years have passed since then and, while Skiddy’s Almshouse continues to thrive, Murphy’s own contributions to the architectural heritage of Cork are not so assured. Jennings Soda Water Factory and Thompsons Bakery have been sensitively repurposed, the stylish chrome and mosaic shopfront of Mayne’s Pharmacy (1959) still dazzles, but Murphy’s offices have not fared so well: the Shield Insurance Building in South Mall has been altered beyond recognition while the nearby General Accident Building (1964) has been replaced. The bottling plant has been dormant since 2007 when Irish Distillers Limited (IDL), the company formed in 1966 by the merger of CDC with John Jameson and Son and John Power and Son, moved production to facilities in Dublin and Antrim. Our architectural heritage must adapt if it is to remain viable as a legacy for future generations. Cork has a proud tradition of adapting its architectural heritage, finding new uses for historic buildings, blending modern interventions and original fabric with flair, and it is hoped that, with a little imagination, the sleeping giant on the bank of the River Lee, once bustling with the sounds of clinking glass and whirring conveyor belts, will awaken as a hive of activity once more.

Conor English received his Bachelor Degree in Architecture from Dundee University and his Masters Degree from University College Dublin. He works in an architectural practice in Dublin. He is the author of Cork’s Modern Architect: The Work of Frank Murphy (2019), the definitive biography of his granduncle, Frank Murphy, who inspired his interest in architecture.

Conor would like to thank Edwin Uniacke who worked with Frank Murphy & Partners from 1953 to 1973, Peter Murphy of FMP Architects, Dr. Ellen Rowley and Dr. Tom Spalding.

FURTHER READING

Butler, Richard J., “All Saints, Drimoleague, and Catholic visual culture under Bishop Cornelius Lucey in Cork 1952-9” in Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society Volume 120 (Cork: Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 2015), pp.79-97

English, Conor, Cork’s Modern Architect: The Work of Frank Murphy (Cork: Watermans, 2019)

Rynne, Colin, Industrial Ireland 1750-1930: An Archaeology (Cork: Collins Press, 2006)

Spalding, Tom, A Guide to Cork’s 20th Century Architecture (Cork: Cork Architectural Press, 2010)

Back to Building of the Month Archive